R. N. Morris, one of our guest speakers for Dostoevsky Day on 19 February, has shared with us this great blog on revisiting Dostoevsky’s classic novel.

“2016 is the 150th anniversary of the publication of Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, Crime and Punishment. To celebrate, Leeds University is holding a Dostoevsky Day on the 19th of February and I’ll be taking part.

It seemed like a good excuse to read the novel again, especially as Penguin have recently published a new translation. And the translator, Dr Oliver Ready, is going to be there too.

It’s been a few years since I last read the book. The last time I did was when I was writing my own Dostoevsky-inspired novels, which feature Porfiry Petrovich, the investigating magistrate from Crime and Punishment. So, in all honesty, I wasn’t really reading as an average reader would. I was a little too focused on my own purposes.

There is a freshness and an immediacy about this new translation that I really like. The characters come alive with a clarity and energy that’s incredibly impressive. It doesn’t feel like you’re reading a translation – there’s none of that usual stiltedness, particularly in the dialogue. Yes, there are some oddities of expression, but that is as much to do with the different culture and the historic distance. (Thankfully it doesn’t follow the trend of many BBC adaptations, where they make everyone from the past speak like a character from Eastenders. Remember The Ark?)

There seem to be things that I notice in this version that had never struck me before. I would even say the novel makes more sense to me now than it has ever. I’m more awed than ever by its greatness. And, too late I’m afraid, more sensitive than I ever was at the time to the complete effrontery of my outrageous act of literary purloining. In retrospect, I am almost unable to forgive myself for my own ‘crime’. I can only turn my face to the wall and stare at the fascinating flower in the pattern of my wallpaper, as a hot sweat of shame breaks out all over me.

What I had forgotten was the novel’s amazing psychological focus. It’s as if Raskolnikov is being observed under some kind of psychic microscope. Every twist and turn of his thought process is laid out for us. Dostoevsky has entered into the mind of a murderer and he compels us to enter it too. Needless to say, it’s not a comfortable experience.

The narration of the events leading up to the murders, and the murders themselves, as well as the immediate aftermath, could hold their own against any piece of crime fiction writing in any era. It’s the observation of the telling detail that does it for me. There is a remorseless, not to say ruthless, honesty to Dostoevsky’s gaze. He refuses to look away, refuses to flinch, even at the most dreadful moment. And he holds our head in his his grip so we’re forced to look too. For example, he just has to show us the tortoiseshell comb – or the fragment of a tortoiseshell comb – pinning up the old pawnbroker’s hair, the second before Raskolnikov strikes her on the crown of her head with the butt of his axe. Genius.

But with its moral, philosophical, social and religious preoccupations, the book is so much more than just a crime novel.

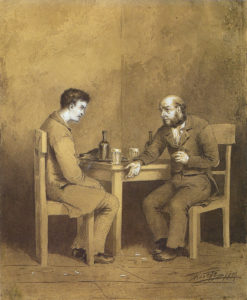

I think one of the most extraordinary sequences in the book is Raskolnikov’s feverish dream in Part One, Chapter V, where he dreams he is a boy again with his father, and together they witness a group of drunken peasants gleefully beat an old nag to death. It’s one of the most savage, humane, awful, devastating, vivid passages in literature. Is it simply the dream of a criminally insane man, or a metaphor for the fate of Russia? Or an elegy for a lost innocence?

So I’m rereading the book at the same time as watching the Netflix documentary everyone is talking about, Making a Murderer (not literally, but you know what I mean). I’m up to about episode 5, so don’t spoil it for me. Anyhow a thought struck me the other night as I was watching it. It was the episode where the learning disabled sixteen-year-old Brendan Dassey is making and retracting his various statements. His mother asks him how he could say the things he said in his ‘confession’. He says he was ‘guessing’ – just like he used to guess when he did his homework. In the end, he writes a letter to the judge trying to set the record straight, with the heartrending postscript “Me and my mum think you are a good judge”. The whole thing just seemed so Dostoevskyan to me, especially as Crime and Punishment features a young man who falsely confesses to the crime.

Dostoevsky used to scour the newspapers for true crime stories, as well as tales of suicide and tragedy. There are references to real crimes in the novel. I couldn’t help thinking that he would have been riveted by the series.”